Studio Ghibli Isao Takahata Interview

Acclaimed director Isao Takahata’s first film in fourteen years is the Academy Award nominated The Tale of The Princess Kaguya.

In 1985, Takahata was one of the founding fathers of animation hothouse Studio Ghibli along with fellow director Hayao Miyazaki and producer Toshio Suzuki Miyazaki, 74, announced his retirement in 2013 and Takahata, who will be 80 this year, says that The Tale of the Princess Kaguya will be his last full-length feature film.

“I have to think of my age and I’m not sure if I have the physical and mental energy for another feature film,” he says. “It took eight years to make this one and I’m thinking about a rest right now.”

Studio Ghibli’s films have won universal praise and a host of international awards and include Grave of the Fireflies, Only Yesterday, Pom Poko (all directed by Takahata), Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle and Ponyo (Miyazaki).

The Tale of The Princess Kaguya, based on a traditional Japanese folk story about a bamboo cutter and his wife who adopt a tiny girl he finds in a bamboo grove, was nominated for the Oscar for the Best Animated Feature Film of 2014.

Takahata was born in Mie Prefecture, Japan, and after graduating from The University of Tokyo with a degree in French literature, he joined Toei Animation Company. His debut as a director was the animated TV series, Ken, the Wild Boy (1963-1965). His first animated film was The Little Norse Prince Valiant (1968).

This interview was conducted through an interpreter at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2014 where The Tale of the Princess Kaguya held its north American premiere.

Why did you want to tell this story?

The original is of course a very well known Japanese story, and I had an idea over 50 years ago that it would be interesting if it were treated in this way. It wasn’t as if I thought I would want to work on it; it’s just that I thought somebody else should make a film out of it. I’ve never really wanted to make a film of this story (laughs). I was only thinking of the Japanese audience, and I realised it would be wonderful if I could present it so that the Japanese audience would think, ‘Oh my, is this the kind of story it really was?’ And also, if I can be presumptuous, ‘Can it be this interesting?’ That’s what I was aiming for.

In what ways will Japanese audiences be surprised by this version of the story?

Initially, on the surface, it looks like it’s faithful to the original story, but there are some little tricks that I’ve put in there. In the original story, we don’t really know that much about the heroine, and how she is feeling, and we can’t really understand her that well. She hasn’t really shown that much interest in worldly things, or in the people of the world, but when she’s told that she has to return to the moon, then she starts crying, and starts regretting that she’ll have to leave this world and go up to the moon. My intention was, ‘Why did she shift her feelings there?’ In the original story, it doesn’t explain that, but in this film, I think I’ve explained it so that we know why she regrets having to go back to the moon.

What did you think you could add to the story?

I thought what needed to be shown was why she came to Earth, and why she must return to the moon. If I made it really obvious then it would not be interesting, so I’ve made it a little bit mysterious, but I’ve shown at least that much, I think.

What is significant about Kaguya’s interest in nature?

I don’t think it’s any particular interest in nature, but the fact that she grew up surrounded by nature is very significant, and really that’s what we have – the world around us is full of nature. Even in the West, poetry is full of nature – British poems are full of nature – or love and human feelings; those are the two main subjects of poems. We’re dealing with the fundamentals of human beings.

Is she doomed as soon as she moves away from nature?

If something else could replace nature to make her happy, then it could have been okay, but the suitors only look at her as a valuable object, like a treasure, as they say. The only desire they express is the ownership of this valuable object, and so she feels very disillusioned.

When did this film begin to become more than an idea?

It was about eight years ago that I started working on this project once again. Of course there were times when I stopped working on it and worked on writing, and other things, but around that time, one morning I woke up and remembered this idea I had to make the story interesting. I presented this to Toshio Suzuki, Studio Ghibli’s producer, and the central figure in this studio. I didn’t intend to necessarily make the film myself, but I just said it might be interesting if someone worked on this film. He said, ‘Well, if you think it might be interesting, why don’t you make it?’ So I thought, ‘Well, okay, maybe I’ll work on it.’

What was the next step for you?

It took me quite a while to flesh out the story. I thought about how we see the moon as a world that is always radiant, because the sun is shining on it, but it doesn’t have colour and it doesn’t have life, whereas the earth is full of colour and full of life. I wanted to use this contrast to show why the Princess Kaguya would want to come to the earth, and why it would be so attractive for her, and such a draw for her to come here. Even in the original story, it’s explained that the moon is some place where people have no worries, and it’s a very pure world. It took me quite a while to make this complete, and then to think about what would be the best way to approach it, and I was helped by quite a few people to do this. With the style, I determined definitely that, whatever I did, my next picture would use the same kind of style of line drawings and sketching, and for the characters, I would ask Mr. [Osamu] Tanabe to draw. I wanted him to draw many pictures to show me, but he wouldn’t draw many (laughs). Often you have the animator draw a lot of pictures, and then you paste them all over the place, but he wouldn’t draw many. My producer and I were surprised! He wouldn’t give me much. But I knew that he could do it, and that he’s a great artist, and I think that really shows in the final product. So, initially, I just left it up to him. I had him do the main animation and drawings. It’s a personal style.

Do you draw at all?

I don’t draw. I do some little sketches to show people what they should be doing, but basically I don’t draw.

How did you start in animation?

I entered a studio after I graduated in university, but I never worked as an animator. Not just me, but many other people who are in the animation business didn’t work in animation. Even the people who were initially animators, once they become directors, and once they start making the films, they don’t draw anymore.

What were the aims when you founded Ghibli?

It was really kind of haphazard, the way we started. When Hayao Miyazaki was to make Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, he asked me to be the producer on that film. I didn’t really want to do it, but he said, ‘Are you just going to ignore our friendship? Are you going to just throw away our friendship and not help me at all?’ So I felt like I had to (laughs). I worked as a producer on that film, but we hadn’t formed the studio yet. Then, the next film, Laputa Castle in the Sky, I was also producer on that. At that point, I said, ‘Well, we might want to start a studio because we do have to present ourselves to the industry, and society.’ Our parent company, Tokuma Shoten Publishing Company, invested in the studio, and we started it. So I don’t think we had any kind of ethos (laughs). We just had to make the studio, and what we were going to do once we made the studio? We were just going to make Laputa Castle in the Sky. That was about all we had in mind.

Were they exciting times?

Yes, they were. We thought it could just fall apart any time.

What was it like to be in that kind of creative environment?

I don’t think we were the kind of creative community or creative company that people normally think of. I didn’t push myself into Miyazaki’s works, and he didn’t push himself into my work, and the producer, Toshio Suzuki, didn’t interfere with our work either. We all kind of left each other alone, and he supported each of us. So I think for both Miyazaki and I, it was much easier to work than in the American system, which might be, ‘We’re going to invest in this product, and so we want you to do this and that,’ and lots of pressure that way. We didn’t have that.

Where were you? Did you have an office?

So, at first we were renting space from another studio, and we just had the staff to make whatever film we were working on. It was at the time that I was making Grave of the Fireflies, in about ’88, and Miyazaki was making My Neighbour Totoro, so we had two studio spaces for two different projects, in the western outskirts of Tokyo. We hardly saw each other at that point, because we were working on our own things. The only person who went between us was the producer (laughs).

Were you surprised by the way the studio grew?

I’m surprised, yes. I don’t know about the other two. Certainly, the talent and genius of Hayao Miyazaki, and the powerful producing capabilities of Toshio Suzuki, I think had a lot to say, but I think we can also think of luck, or miracles, that might have played a part as well. I think failure is just part of the way things are naturally done, and the fact that we haven’t failed is a very unnatural thing, and surely can’t continue forever. You might ask the producer, Tohio Suzuki, because he’s the one who has written something like ‘The Philosophy of Studio Ghibli’, which I haven’t read (laughs), but he’s probably spelled it all out in that book. There’s also a documentary, which I haven’t seen either, that talks about that – The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness. There might be a secret in that, but I haven’t seen that one either. I don’t really believe in what they might be saying.

What’s the future for Studio Ghibli?

Since I’m not involved in the operations of the studio, I don’t really know what will happen, but I think it’s very likely that the films will be made in perhaps a slightly different form than they have been in the recent past. Even though Miyazaki has said that he is retired from making feature length films, I’m sure he’ll continue to work on smaller projects, and maybe shorts, and so as projects come up, there’s certainly a great possibility that the studio would be able to create and produce feature films, but there may not be that possibility, also. I don’t think anyone at the studio really knows what’s going to be happening. Mr [Yoshiaki] Nishimura is the producer of The Tale of The Princess Kaguya, and the film that Studio Ghibli released after that, this past summer, which is called When Marnie Was There – he also entered in as producer of that partway through. It’s producers like him that I wonder what they’re thinking of, in terms of the future of Studio Ghibli.

What will you do next?

In my case, since I have to think of my age, I’m not sure if I have the physical energy or the mental energy to make another feature film, and also whether there is the money that might be invested in a film that I might want to make. Of course, I would have to have an excellent producer who could gather that money, perhaps, for me to be able to make it. In terms of animators, of course there are talented top animators that could work on all the drawings. Even for this project, we hired the majority of animators outside of Studio Ghibli, so I know we can hire people on a project basis. I think all those conditions would have to be met for me to make any film in the future.

How many people work at the studio?

About 300.

Will we see a new generation of animators begin to take the mantle?

Well for example, Disney, at one point, was almost going to wither away, but it had the assets that it had, and it was resurrected, and now it’s a large company. There could be a completely different direction and a completely different force that comes into being, in terms of Japanese animation. Or animation itself might decline. I’m not sure.

Do you find your output influenced by Western animation?

At my age, I don’t know if I can be influenced that much anymore. Of course, in my youth, I really respected and honoured Disney and what he had done, but I always thought it was too different from the way things are in Japan to really take something from that and be able to utilise it. Our starting points were very different, I think. For example, when you make animation in films in English or Japanese language, they’re very different. In Japanese, we can talk just by moving our mouths, without large gestures, and that’s a normal way of talking in Japanese, whereas you look at American or Western animation – and there’s too much action, or the action is too broad to fit into a Japanese context, or to be an influence on us. If we use those kind of large gestures, then people say, ‘That smells like butter,’ meaning, ‘It’s too Westernised.’ It’s a sort of derogatory sense. In that way, even animation is very culturally bound, so I think we need to be careful about influences. For example, my Anne of Green Gables, the television series that is of course based on a Canadian girl – she talks a lot, and of course she would be speaking in English, and using gestures probably, but if I had shown that to a Japanese audience, that would look very strange, so I didn’t use many gestures. It’s been well-received in Japan, and it’s a very popular TV series, but now, when that is shown in the West, dubbed into other languages, then I feel like, ‘Oh, is it really going to work in those other languages?’ – for example in Italy, where people use a lot of gestures to talk. So if it’s dubbed in Italian, and the girl’s just standing there, straight, without any gestures, isn’t that going to seem a little off to them? I worry about the kind of reception that it gets in the West.

Broadcasting Press Guild Awards Winners 2015

‘Biopic’ dramas, based on the lives of real people, have picked up more top prizes at the 41st Broadcasting Press Guild Awards, voted for by journalists who write about TV and radio. This morning winners and BPG members attended a celebratory lunch sponsored by the Discovery Channel.

Hard on the heels of Eddie Redmayne’s Oscar and BAFTA success for his portrayal of Professor Stephen Hawking, Sheridan Smith has won the BPG’sbest actress award for her performance as the young Cilla Black in the ITV drama Cilla. Toby Jones has been named best actor for his role as Neil Baldwin, the relentlessly upbeat kit-man at Stoke City Football Club, whose life was dramatised in Marvellous on BBC Two. Marvellous won the award for best single drama and BBC Two also won the award for best drama series, withThe Honourable Woman.

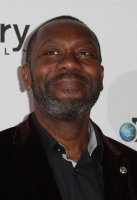

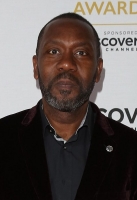

Forty years after his TV debut in New Faces, Lenny Henry receives the BPG’s highest honour, the Harvey Lee Award for Outstanding Contribution toBroadcasting. It recognises his contribution to Comic Relief, which began 30 years ago, and also his campaign for greater diversity in broadcasting, which is finally starting to change policies at the UK’s major broadcasters. Henry is breaking off from rehearsals for tonight’s Red Nose Day telethon to attend the ceremony.

The award for best radio programme has gone to BBC Radio 4 for Germany: Memories of a Nation, presented by Neil MacGregor, director of the British Museum. Jane Garvey, the presenter of Woman’s Hour, also on Radio 4, is named radio broadcaster of the year.

Channel 4 has taken two awards for factual television. Benefits Street – which attracted front-page headlines and fostered debate and controversy – won the award for best documentary series and Gogglebox won the BPG award for best factual entertainment, for the second year. The award for best single documentary went to Baby P: The Untold Story on BBC One.

W1A, BBC Two’s spoof documentary about the BBC and its management, was named best comedy. Crackanory, the star-studded storytelling series for adults on UK TV’s Dave, won the multichannel award.

Writers were well represented at this year’s awards. Sally Wainwright was a runaway winner of the BPG writer’s award for Last Tango in Halifax and Happy Valley, both on BBC One. And the BPG Breakthrough Award went to the brothers Harry and Jack Williams, who wrote another hit BBC One drama series, The Missing.

The final award, for Innovation in Broadcasting, went to Vice News, the online start-up which was set up in London only a year ago as part of Vice Media, and which has produced ground-breaking reports on the world’s trouble zones for young audiences.

Full list of winners and a gallery pf pictures below:

Best Factual Entertainment Gogglebox

Best Single Drama Marvellous

Best Drama Series The Honourable Woman

Best Single Documentary Baby P: The Untold Story

Best Documentary Series Benefits Street

Best Multichannel Programme Crackanory

Radio Programme of the Year Germany: Memories of A Nation

Radio Broadcaster of the Year Jane Garvey - Woman’s Hour

Best Entertainment/Comedy W1A

Writer’s Award Sally Wainwright

Best Actress Sheridan Smith

Best Actor Toby Jones

Breakthrough Award Harry and Jack Williams, writers of The Missing

Innovation in Broadcasting Award Vice News for The Islamic State and other original commissions

Harvey Lee Outstanding Contribution to Broadcasting Lenny Henry